There is the tick and whir of complex machinery.

There is the tick and whir of complex machinery.

I hear its purr and hum, long before I enter the house, on a sidewalk in suburban Los Angeles, misted with the lilac haze of jacaranda blossoms. I hear it - above the clicking of cicadas, the drone of lawnmowers, the lazy bark of a distant dog - the soft, subtle, shifting of gears…

It's the sound of the Machine…

The Time-Machine…

I was scarcely into my teens when I first hitched a ride: seizing paperback after paperback with wildly fantastical titles - Something Wicked This Way Comes, The Golden Apples of the Sun and (over fifty years old but still fresh with the scent of kerosene) Fahrenheit 451.

Riffling through their pages, I was yanked mercilessly out of Now, spun around, and hurled - screaming with fear, whooping with delight - through time and space to Yesterday and Tomorrow by the wild imagination of the man at the controls of the Time-Machine: Ray Bradbury.

Now, as I’ve happily done many times in the last thirty years, I’m entering the machine shop, the mad-doctor-laboratory where the inventor is ready and waiting to whisk me off - to where?

To lemonade-sweet, small-town America at the turn of the century?

To lemonade-sweet, small-town America at the turn of the century?

To labyrinthine tombs of ancient Egypt, ankle-deep in mummy-dust?

To steaming cretaceous jungles, where dinosaurs rage, rip and roar?

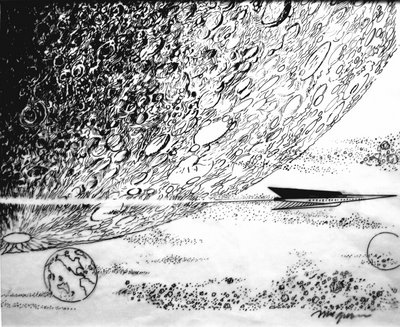

Or to a lunar landscape where future pioneers head for the far-flung stars?

If this were your first visit, you’d say that Ray Bradbury cut a curious figure, a sort of literary version of Professor Brown from Back to the Future. With flyaway, white hair and bottle-bottom spectacles, he sports a pair of khaki shorts worn (with braces) over a conventional shirt and a tie decorated with a vivid whale motif – appropriately enough, since this is the man who wrote the screenplay for John Houston’s Moby Dick.

Born 22 August 1920, he is has just turned eighty-eight years old. Widowed and robbed by a stroke of some of his mobility, he is, nevertheless, as mentally agile and emotionally excited by life as any spring-heeled, eight-year old leaping through the slow-motion world of grown-ups.

This time-machine is not some H G Wellsian contraption of polished brass and mahogany, but a mind alive with memories and precognitions: recalling the very moment of his birth and the sudden terror of being expelled from the warmth and safety of the womb; and anticipating the hour in which the machine will finally run down…

But first a memory of that book about book-lovers and book-burners, written more than half-a-century ago, in which Bradbury foresaw a time when books were banned and the firemen’s job was not to extinguish fires, but to ignite them. Fahrenheit 451 was and is a metaphor for freedom of thought - doubtless the reason why Michael Moore spoofed the title (somewhat to Bradbury’s annoyance) for the movie, Fahrenheit 9/11.

But first a memory of that book about book-lovers and book-burners, written more than half-a-century ago, in which Bradbury foresaw a time when books were banned and the firemen’s job was not to extinguish fires, but to ignite them. Fahrenheit 451 was and is a metaphor for freedom of thought - doubtless the reason why Michael Moore spoofed the title (somewhat to Bradbury’s annoyance) for the movie, Fahrenheit 9/11.

The fact is, the book-burning age depicted in Fahrenheit 451 (and triumphantly realised in François Truffaut’s 1966 film), still haunts us – even in an age when the cold war is no more than a chilly memory and when electronic communications appear, however spuriously, to offer new security to words, thoughts and ideas…

Some fears never die and ever since Bradbury first set a match to the book-stacks of the world, we have shuddered to think that Prospero, Alice, Mr Darcy, David Copperfield, Long John Silver and the Wizard of Oz might, some mad day, blaze to a crisp and smoulder into ash. For Bradbury, too, the threat of the flame still quickens the pulse.

“When I was young,” he says, “I was a child of the library: I never went to college, the library was my education which is why you mustn’t ever touch my University! Endanger it by setting fire to the libraries of Alexandria or by burning books in the streets of Berlin and you have committed a personal crime against me!”

How could it not be a threat to a man living in a room lined with books, in a house shelved, stacked, piled and heaped with volume upon volume.

He met his late wife, Marguerite – Maggie – when she worked in a bookstore, but she was always on to him about the ever rising tide of book-print: “Maggie could never get me to throw out a book or give it away! She’d say, ‘Why are you keeping that?’ And I’d say, ‘Wait! You never know; a year may come, when I pick up and open a book that I’ve not opened in years and stumble across a great idea for a story or a poem or a play…’ I can’t help it; I’m a library person.”

It was in a library that Fahrenheit 451 blazed its way onto the page. When “a house full of daughters” was robbing Bradbury of sufficient peace and quiet to write, he holed himself up in the basement at UCLA, renting a typewriter for 10 cents a half hour and “writing like hell and at the top of my lungs”.

Nine days and $9.80 later, he had the manuscript of F451. “I had no idea that all these years on it would still be read, still mean something. Or that I’d still be writing and living a life walled-up and bricked-in by books.”

His recommendation, therefore, to anyone who doesn’t quite know what to do with their lives is this: “Go sleep in a library; go live there; rent a room in the basement and come up every day and soak yourself in literature, until you open a volume, discover a mirror-image of yourself and say: ‘My God, I didn’t know I lived in a book! Why didn’t anyone ever tell me that this writer existed as my mentor and teacher, as an ambiance in which I can swim?’”

Bradbury’s voice is fired with passion. “Seize and embrace that book and that author will be your author: the one who makes you want to jump out of bed in the morning and live for ever as if every day is New Year’s Day!”

I recall the day, one blistering hot summer of childhood, when I opened a book with a black cover and a tangle of purple Goyaesque grotesqueries and fell, once and for all, under the Bradbury spell.

I recall the day, one blistering hot summer of childhood, when I opened a book with a black cover and a tangle of purple Goyaesque grotesqueries and fell, once and for all, under the Bradbury spell.

“Good!” he responds. “That’s good! Because I’m not really a fantasy writer, a science-fiction writer!” What then? A magician, perhaps? “No! I’m a teacher! My books are schoolbooks on life. My task - every writer’s task, the task of any good book - is to teach you what you are and what you want to become. Teach you to be fantastically alive!”

And to love? “Oh, yes! All my books are love-books. All of the great events of my life are based on the wonderful accidents of love and my willingness to confess that I am very weird!”

This is the man who took us by the hand and enticed along the carnival midway, lifted the flap of shadow-filled tents and ushered us into the twilight world of freaks and monsters.

“When I was three years old I saw Lon Chaney in The Hunchback of Notre Dame and thought, perhaps, I was a hunchback and that’s why I loved him. I thought maybe I don’t know it, but there’s a hunchback somewhere inside me. That was Chaney’s secret: he had all these hunchbacks, gargoyles and phantoms hidden away inside him - and allowed you to discover them inside you!”

Growing up in ‘thirties Hollywood, Bradbury haunted the studios, star-spotting and autograph-hunting; that's him, thirteen years old, arm-in-arm with legendary comic, George Burns.

Growing up in ‘thirties Hollywood, Bradbury haunted the studios, star-spotting and autograph-hunting; that's him, thirteen years old, arm-in-arm with legendary comic, George Burns.

The young Ray sold newspapers on street corners to earn the price of cinema-tickets. Mornings, afternoons, evenings were spent in the dark watching the exploits of the travellers following the Yellow Brick Road; entranced by ballet-dancing hippos and ostriches; shuddering at the terror that was King Kong; marvelling at the dinosaurs in The Lost World; shedding tears of laughter and sadness as the Little Tramp disappeared over the brow of the hill into the sunset.

“Then late night on Fridays, I’d go to where the boxing fights were taking place and see Cary Grant and Mae West coming out. I’d not be home till midnight. Fourteen years old and my mother and father let me roller-skate around Hollywood on Friday nights! Why? Because they trusted me not to get into trouble and because they knew I was in love with this medium of film. In love with Chaney and Chaplin, Karloff and Disney.”

Alongside the books pulled indiscriminately from the library shelves – Shakespeare, Dickens, Shaw, Chesterton and Poe – there were the comics and the cartoons. “I was nine years old when Buck Rogers changed my life.”

Bradbury sends me into the next room, where, framed and hanging on the wall, is a single, yellowing panel of a comic strip clipped from a newspaper with a caption that sums up the forward-visioning philosophy of that hero of the twenty-fifth century: “The only boundaries are our dreams”.

On my return, I repeat the caption to Bradbury. “Yes! And that’s the truth! I saw the future in one single Buck Rogers strip and it changed my life for ever.” Without Buck, we might never have read of those intrepid explorers leaping aboard their silver locust spacecraft and blasting off for the Red Planet in The Martian Chronicles.

On my return, I repeat the caption to Bradbury. “Yes! And that’s the truth! I saw the future in one single Buck Rogers strip and it changed my life for ever.” Without Buck, we might never have read of those intrepid explorers leaping aboard their silver locust spacecraft and blasting off for the Red Planet in The Martian Chronicles.

All this was a rare apprenticeship for a writer, but a costly one: “My last year in high school, I didn’t have any friends… I thought I had friends, but I didn’t! They had nothing but contempt for me, because I was different! I was this freak! I loved books and films, circuses and magic-shows; I loved Tarzan, dinosaurs, comic strips and rocket ships. Basically, I loved all the wrong things!”

Unrepentant, Bradbury clung to his enthusiasms, pursued his own dream: to be a writer. “My last year in high school: the Annual contained a photograph of me and the quote: ‘Likes to write short stories and headed for literary distinction’. I was seventeen and I couldn’t write a goddam thing! But some secret in me gave me that quote and by the time I was twenty-five, I was selling stories to pulp magazines and making, maybe, $10 to $15 a story. But it was slow progress; I wasn’t being published in any of the big magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and I was very unhappy.”

Bradbury was so unhappy that a friend recommended that he consult a psychiatrist. “He charged $25 for forty-five minutes. I couldn’t afford longer. He asked what my problem was and I said, ‘I want to be the greatest writer that ever lived…’ Can you imagine his reaction? This twenty-five years old saying that his problem was not having become the world’s greatest writer! He didn’t show it in his face; he just sat there and then, at last, said, ‘Well, you’re going to have to be patient aren’t you?’”

The psychiatrist’s advice was to look up the lives of great writers and see how long it had taken them to get established: for some, years and years; for others - like Herman Melville – never in their lifetime. “So I read their life-stories, kept on writing, and learned that you have to be accepting of your own ego – however preposterous it may be - and to make do with yourself and get your work done.”

Bradbury’s work is all about us, bookcases stacked with his books, a hundred or more: novels, short stories, poems, plays, memoirs and essays - from The Dark Carnival to Farewell Summer - full of metaphoric word-pictures, that rattle about for ever in your consciousness like fair-ground skeletons: a backwards-running carousel, spinning people round and back to their childhoods; a man who inherits the vocation of the Grim Reaper and is forced to wield the scythe against his own family; the time-traveller who steps on a primeval butterfly and changes the course of history; the automated house on Mars which goes on mechanically serving a family long after they have fallen victim to the final apocalypse.

Bradbury’s work is all about us, bookcases stacked with his books, a hundred or more: novels, short stories, poems, plays, memoirs and essays - from The Dark Carnival to Farewell Summer - full of metaphoric word-pictures, that rattle about for ever in your consciousness like fair-ground skeletons: a backwards-running carousel, spinning people round and back to their childhoods; a man who inherits the vocation of the Grim Reaper and is forced to wield the scythe against his own family; the time-traveller who steps on a primeval butterfly and changes the course of history; the automated house on Mars which goes on mechanically serving a family long after they have fallen victim to the final apocalypse.

At eighty-eight, he shows no sings of slacking. Twenty years after many people have retired, Bradbury is still eagerly minting new metaphors, new schoolbooks for life. “The fuse keeps on burning,” he laughs, “the explosions continue!”

And the prospect of that day when the machine stops?

“Oh… I’m surrounded by stopped machines, aren’t I?” He pauses. A moment of reverie. Then he sighs, less out of weariness than with resolve: “So, as I say, you get your work done… You get your work done…”

“Oh… I’m surrounded by stopped machines, aren’t I?” He pauses. A moment of reverie. Then he sighs, less out of weariness than with resolve: “So, as I say, you get your work done… You get your work done…”

That boy who once lived in the library would have been astonished to see how many books bearing his own name are now to be found in that library. But if the man today could tell that boy back then anything, what would it be?

Bradbury looks long and intently at me and then breaks into a broad smile: “Nothing! I wouldn’t have to say anything to him, because he always knew… It was always inside him… Always, from the day he was born…”

From the very moment the Time-Machine first hummed into life, for as long as the machinery continues to run – and, indeed, beyond…

For every time some child in a future library, a hundred years hence, opens a Bradbury book, the miraculous machine will, once more, jump-start into whirring, fizzing life…

Images: Bradbury photograph by Marissa Roth for The New York Times; book covers from Bradbury Media

Read my thoughts on Ray Bradbury's The Golden Apples of the Sun and Something Wicked This Way Comes.

➠ HOME & MENU